Interested in Ottoman Era ?

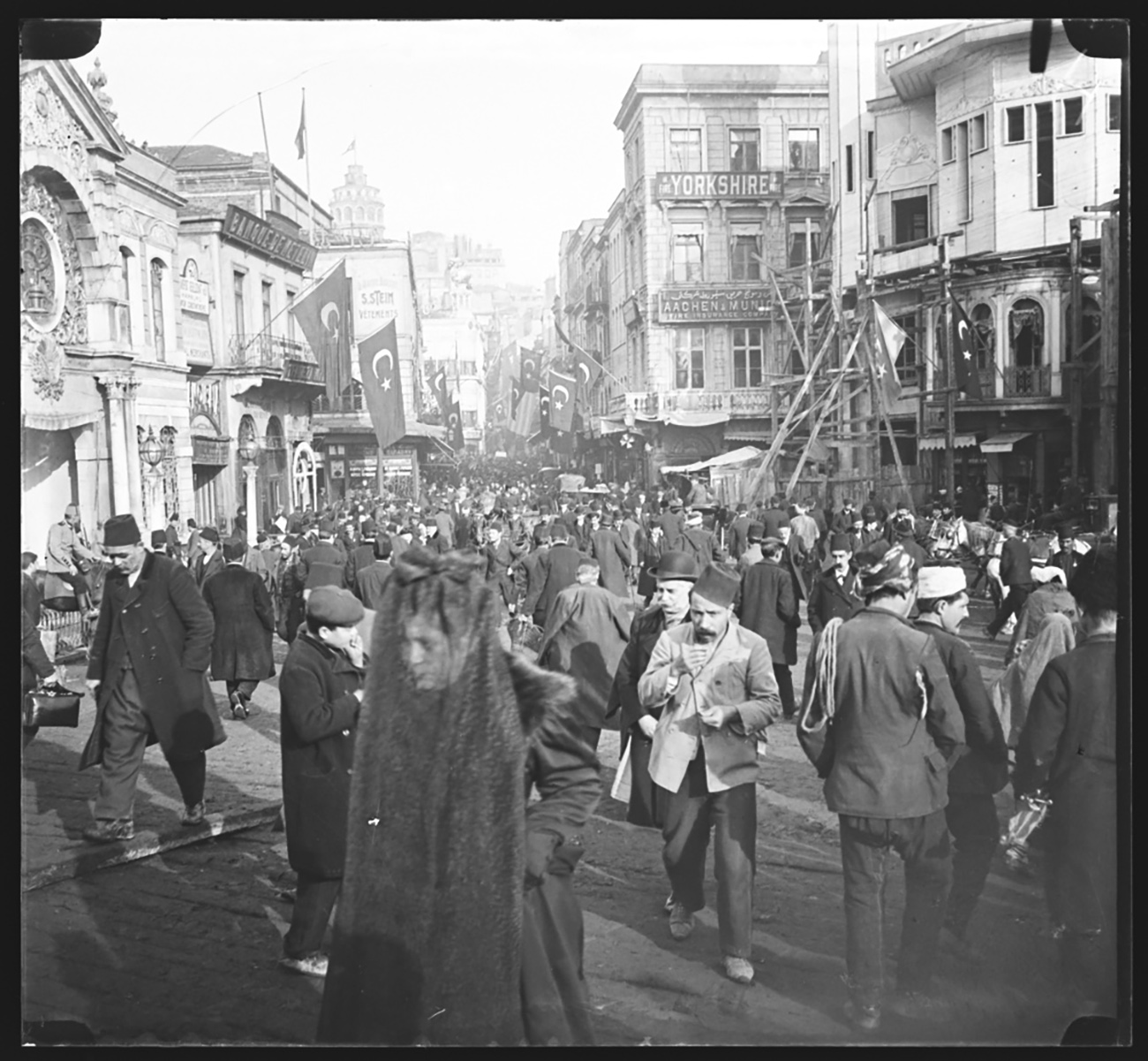

In the 1980s the French collector Pierre de Gigord traveled to Turkey and collected thousands of Ottoman-era photographs in a variety of media and formats. The resulting Pierre de Gigord Collection is now housed in the Getty Research Institute, which recently digitized over 6,000 of the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographs, making them available to study and download for free online.From albumen prints to lantern slides, glass negatives and albums, the collection documents landmark architecture, urban and natural landscapes, archaeological sites of millennia-old civilizations, and the bustling life of the diverse people who lived over 100 years ago in the last decades of the waning Ottoman Empire.The digitization project focused on photographs from the nineteenth century until World War I (Series I–VIII), resulting in 3,750 individual records of digital files. Research Institute photographers such as Lyndsey Godwin-Kresge took thousands of materials that are difficult to find, as they are preserved in the vaults with limited circulation, and transformed them into digital files.Armchair Traveling to the Ottoman Era

The digitization of such diverse media, from long panoramas (Series IV) to pocket-sized cartes de visite, presented different challenges. The 10-part panorama of Constantinople required stitching separate albumen prints together to create an imposing panoramic view of the skyline of Istanbul and the Bosporus in 1878. Now it may be viewed on a screen in its entirety.Photographing the 50 hand-colored slides from the Viennese business Josef Sengsbratl necessitated calibrating both front and backlighting to capture the warm tones of the color images as well as the business credit name and address. At the turn of the century, people would project these slides on a screen in educational settings or in private homes for personal entertainment, allowing them to become armchair travelers. Through these images they learned about Turkish women and men, crafts and trades, the landmark architecture of the Ottoman capital, government functionaries, and the geopolitics of the region.

Porters Carrying Rope, Josef Sengsbratl. Hand-colored glass lantern slide. Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. The Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Busy Street, Constantinople, 1890, unknown photographer. Glass plate negative. Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. The Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

First-Person Perspectives

The digitization of over 60 photographic albums (Series I and II) allows us to access the unique personal narratives of collectors and photographers who traveled through Ottoman Turkey. In the album Türkei = Kleinasien 1917–1918 (Turkey = Asia Minor), a German military officer, yet to be identified, dedicated his photographs to a faraway “beloved Pauline.” This album documents—in great contrast to his romantic dedication—the presence of the German army in Turkey during the Armenian genocide.In accordance with standard digitization practices, the album was photographed not only page after page but also image after image, allowing viewers to experience the images close-up in detail. The neat calligraphy of the image captions and well-composed arrangements of the photographs reveal the care the officer took in documenting the journey and mission. Photographs of cities, markets, and sites of destruction are recorded along with encounters with government functionaries such as the minister of war, Enver Pasha, the highest-ranking perpetrator of the Armenian genocide.

Türkei = Kleinasien 1917–1918, page 7. Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. The Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14

Türkei = Kleinasien 1917–1918, page 16. Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. The Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

An Obliterated Past

Scholars have already used the Gigord collection for research in multiple disciplines, from Turkish architecture, archaeology and antiquities, Byzantine and Islamic art, postcolonial studies, and the history of photography.Here on The Iris, artist Hande Sever recently highlighted the central role Armenian photographers played in shaping Turkey’s national cultural history and collective memory. Sever notes how the archive offers visual records of an obliterated past, a world that disappeared due to ethnic conflict and cleansing.The Gigord digitized images, with their records of people, architecture, urban spaces, and landscapes of a bustling world a century ago, make a noteworthy comparison with the work of the late Armenian photographer Ara Güler (1928–2018). His photographs and family history document the aftermath of World War II. Güler, who lost his grandparents to the Armenian genocide, worked for the photo agency Magnum and built an archive of 900,000 photographs.Orhan Pamuk, the renowned Turkish writer who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2006, used images from Güler’s archive to illustrate his novels set in 20th-century Istanbul. He also paid tribute to Güler in a New York Times opinion piece. Pamuk wrote that A look at nineteenth-century Turkey through photographs.er’s photographs are not just beautiful—they are important because of the connection between visual records and personal memories:A street might remind us of the sting of getting fired from a job; the sight of a particular bridge might bring back the loneliness of our youth. A city square might recall the bliss of a love affair; a dark alleyway might be a reminder of our political fears; an old coffeehouse might evoke the memory of our friends who have been jailed. And a sycamore tree might remind how we used to be poor.

Galata Bridge, about 1875–89, Guillaume Berggren. Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. The Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Losing the Aura of Materiality

In the digital environment, these images are removed from their original physical context. Presented without their physical supports, formatting, or sense of scale, some aspects of their materiality may elude us. Yet increased access to the photographs allows us to visualize and experience the past and create relevant connections to the present.For instance, the peaceful intimacy of this scene of a man reading a letter to two girls transcends time. One can imagine how this photograph would have evoked indelible memories for whoever owned this image, keeping it treasured in a drawer, pinned to a wall, or perhaps mounted in a private family album.

Man Reading to Two Girls, 1890, unknown photographer. Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. The Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Clockwise from top left: Kurdish Bandits Captured and Executed by the Turkish Gendarmerie, Trabzon, Couple from Trabzon; Views of Port with Streetcars, 1885–95, unknown photographer. The Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Discover more from Islam Hashtag

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.