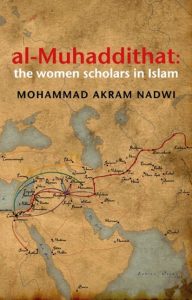

Al-Muhaddithat: The Women Scholars in Islam.

For Muslims and non-Muslims alike, the stock image of an Islamic scholar is a gray-bearded man. Women tend to be seen as the subjects of Islamic law rather than its shapers.

It surprises people to learn that women, living under an Islamic order, could be scholars, that is, hold the authority that attaches to being knowledgeable about what Islam commands, and therefore sought after and deferred to.

The typical Western view is that no social order has (or aspires to have) more ‘religion’ in it than an Islamic one, and the more ‘religion’ a society has in it, the more restricted will be the scope in that society for women to enjoy agency and authority. Behind that is the assumption that religion is ‘really’ a human construct, done mainly by men and therefore done to secure advantages for them at the expense of women. Muslims, of course, do not share this view.

The scholars are agreed that there is no difference between men and women in any type of narration, and that the two are alike in the right (and duty) to receive, hold and convey hadlth. The proofs for this are overwhelming and go back to the very first occasion that Islam was preached in public.

We cannot be surprised by this, given that the study of hadlth is not an idle or leisure pursuit, but a means to understand the guidance of the Quran and then implement it in personal life and in society. The lawfulness of receiving and transmitting hadlth is based on the duty of all Muslims to know their religion (dm) and put it into practice: neither men nor women are exempted or excluded from this duty

The Sunnah is particular about treating sons and daughters equally. Al-Bazzar has cited the hadith from Anas ibn Malik RA that there was with the Prophet a man whose son came to him: the man kissed the boy and sat him on his lap. Then his daughter came and he sat her in front of him. Allahs Messenger SAW — said to the man: Why did you not treat them equally?’

The Quran rebukes the people of the jahilijyah (the Ignorance before Islam) for their negative attitude to women (al-Nahl, 16. 58—59): When news is brought to one of them of [the birth of a girl, his face darkens, and he is chafing within!

He hides himself from his folk, because of the evil he has had news of. Shall he keep it in disdain, or bury it in the dust? Ah — how evil the judgement they come to! The costly prospect of bringing up a daughter (a son was expected to enhance a clan’s military and economic potential) perhaps explains this negative response to the birth of a girl. Burying infant girls alive was a custom among some (not all) of the Arab tribes of the time. The Quran warns of retribution for this gross atrocity.

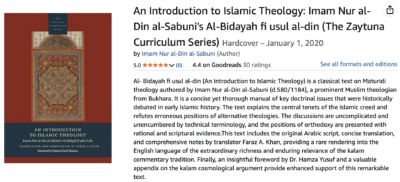

Mohammad Akram Nadwi, a 43-year-old Sunni alim, or religious scholar, has rediscovered a long-lost tradition of Muslim women teaching the Koran, transmitting hadith (deeds and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) and even making Islamic law as jurists.

Akram employs a potent debating strategy: he compares the status quo to the age of al jahiliya, the Arabic term for the barbaric state of pre-Islamic Arabia. (Osama Bin Laden and Sayyid Qutb, the godfather of modern Islamic extremism, have employed the comparison to very different effect.) Barring Muslim women from education and religious authority, Akram argues, is akin to the pre-Islamic custom of burying girls alive. “I tell people, ‘God has given girls qualities and potential,’ ” he says. “If they aren’t allowed to develop them, if they aren’t provided with opportunities to study and learn, it’s basically a live burial.”

This book is an adaptation in English of the prefatory volume of a 40-volume biographical dictionary (in Arabic) of women scholars of the Prophet s hadith. Learned women enjoyed high public standing and authority in the formative years of Islam.

For centuries thereafter, women travelled intensively for religious knowledge and routinely attended the most prestigious mosques and madrasas across the Islamic world. Typical documents (like class registers and ijazahs from women authorizing men to teach) and the glowing testimonies about their women teachers from the most revered ulema are cited in detail. An overview chapter, with accompanying maps, traces the spread of centres of hadith learning for women, and their eventual decline. The information summarized here is essential to a balanced appreciation of the role of women in Islamic society.

Neverthless, Akram says he hopes that uncovering past hadith scholars could help reform present-day Islamic culture. Many Muslims see historical precedents — particularly when they date back to the golden age of Muhammad — as blueprints for sound modern societies and look to scholars to evaluate and interpret those precedents. Muslim feminists like the Moroccan writer Fatima Mernissi and Kecia Ali, a professor at Boston University, have cast fresh light on women’s roles in Islamic law and history, but their worldview — and their audiences — are largely Western or Westernized. Akram is a working alim, lecturing in mosques and universities and dispensing fatwas on issues like inheritance and divorce.

In the Book, The author stresses that Women attained high rank in all spheres of knowledge of the religion, and, as this book will show, they were sought after for their fiqh, for their fatwas, and for tafsir. Primarily in the book , the author is concerned with their achievement and role as muhaddithat. In the first Section he sets out the overall impact of Qur’an and Sunnah in changing attitudes to women; in the second section, I explain different dimensions of the change as instituted or urged by Qur’an and Sunnah; in the third what the women themselves did in the formative period of Islam so that men, in a sense, had to accept that change.

Hadith scholars did not distinguish between men and women

teachers as being more or less worthy for being men or women.

They paid the same attention to preserving accurately the wording of hadiths narrated by women as to those narrated by men.

In the later period interest in seeking out women scholars is a

part of the effort to get higher isnads. If a woman shaykhah

outlived all the men in her generation, she would attract a lot of

students, who would come to study with her in order to make

their isniid higher.

A Must Read Book and I definitely recommend it . If you have a daughter in your home, inspire her with this book , You can get it from Amazon

Read more Book Recomendations

Follow us in Facebook

Discover more from Islam Hashtag

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

MAY ALLAH BLESSED YOU FOR YOUR RESEARCH

We will be integrating best Sunni Muslim Proposals in Hyderabad, and the Hyderabadis residing around the globe We have been working as Muslim Matrimony in Hyderabad since 2009, and in last couple of years we have elevated as the Best Muslim Matrimonial services provider in Hyderabad.